Flashbacks of Memories to be Forgotten

Everything I hold onto has a purpose; a lesson. When the purpose has been fulfilled—mastery gained through practice, with patience and discipline—I perform a ritual to prepare the body for release.

A Ritual of Release & Forgiveness

I sealed this shoe box with a promise not to open it until after the publication of I’m Not Wearing Any Pants: Undressing a Diagnosis, expected in 2026. Primary drawings of a flattened pair of pants, and a skirt that looks more like broccoli than clothing, childishly decorate the lid. The brand of shoes belong to Katy Perry, a significant figure in my 20s and 30s, through marriage and divorce. The alter-ego rebelliously deconstructed her Christian beliefs in the digestible form of pop culture.

I can grow up and away from this, too, in my own way; I can be a person separate of the people who thought to create me to be

a person separate of the people who thought to create me to be a person separate of the people who thought to create me to

be. now i /\m: creator

I all but forgot what the box contained, which was the point. These were things hidden from sight so they might also be hidden from mind; things that trigger living memories and ignite the body.

what is concealed must be healed

i /\m: forgiven

I decided to open the box early to aid the book editing process.

The compiled manuscript—only a fraction of 24 year’s worth of journaling across print and digital mediums—sat at a hefty 675,000 words; the cutting room floor has only seen 158,000. The shoebox content helps me, as writer, identify where to focus the editorial eye next.

A glass candle wrapped in a True Reflection affirmation from 2021 tied with a red and white thread.

she is love. this is my true reflection. she is an artist. she is unafraid to love who she loves. she is unafraid to share her love and voice and process with all who choose to listen. she waits patiently, with wisdom and discernment for the invitation. she loves her shadow, and the secrets we share in the in between—for only us. she is slow and graceful: methodical. she can be quick and clumsy: joyful spontaneity! she has good posture and composure: she moves! she is an old soul and she is innocent. she lives the life she loves because she knows her worth and her value. she knows what she needs, what she wants, and expresses without apology. she is a dew drop and she is a storm. she is the rose petal and she is the thorn. she is wise and drinks from the fountain of youth. she is true.A palm-sized gold framed school photo of me at 12-years old; <f/>other’s favorite. It sat on his desk for years. I took it when I last lived with him, during Covid. Who says the estranged aren’t sentimental? Does sentiment require hope? Hope for what?

The only bible I have is <m/>other’s from her youth, a graduation gift at the ceremony from The Order of the Rainbow for Girls, with gold-lined pages. Separate from the United Pentecostal Church, pre-<f/>other’s influence? The stack of bibles collected in my lifetime, I left behind—in a closet, with the parents, spiritual prison—those inscribed with notes from my ghosts, the inner children, and those gifted to me as a blessing: a bible <f/>other preached from, a bible <m/>other made notes in, and grand</m>other’s bible, dedicated to me with a poem on the day of my birth.

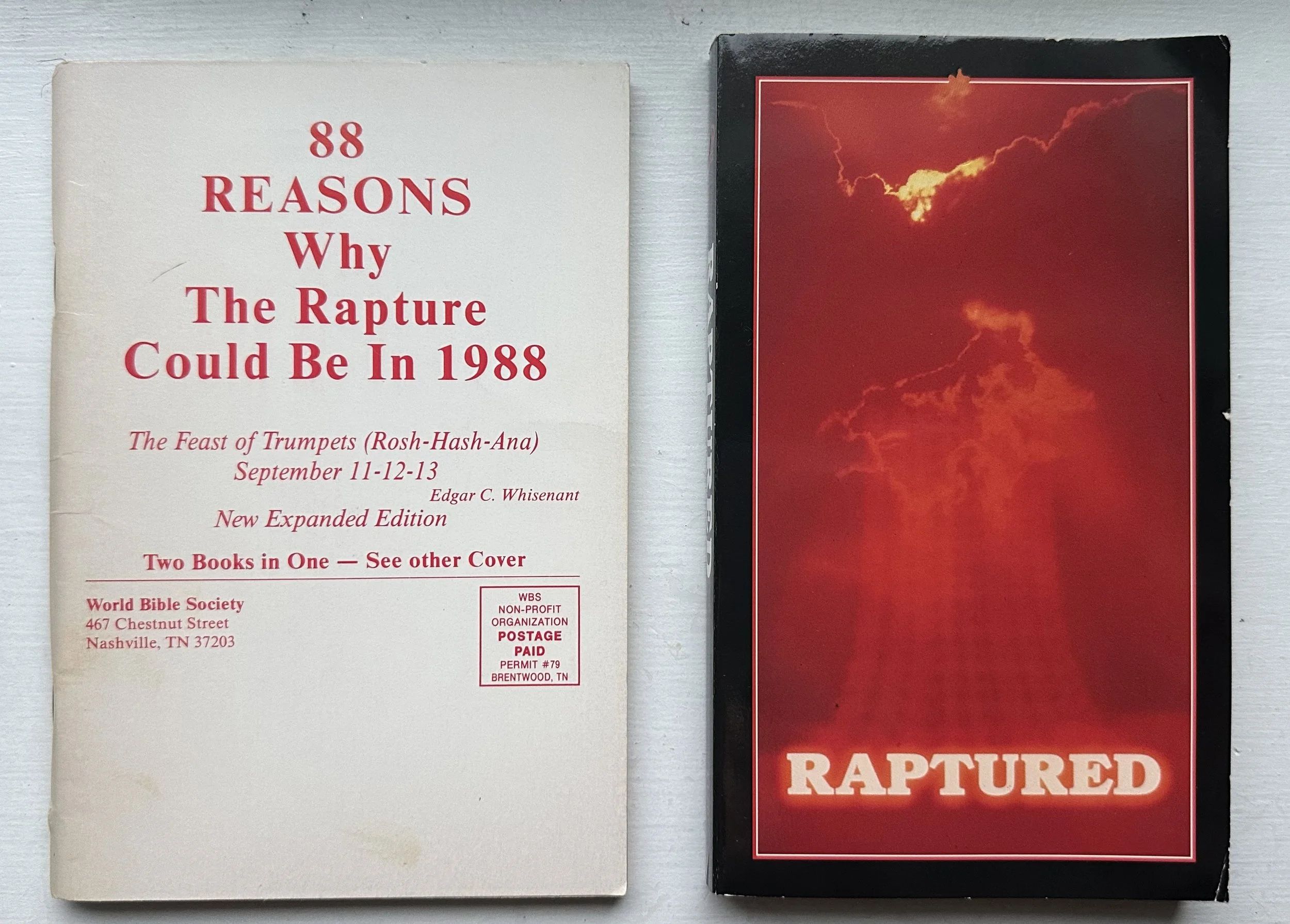

RAPTURED: A Novel on The Second Coming of The Lord by Ernest Angley, published in 1950, was handed to me by <br/>other. He was reading Stephen King but this wasn’t just another horror story. This was a novel interpretation of coming soon true events. By age seven, I had a healthy fear of the Christian apocalypse and I did not expect to live for long. The idea of the rapture and Jesus coming “as a thief in the night” terrified me, and I pretended to speak in tongues to save the soul—a lie that cloaked me in shame. I was consumed with survival and being good enough until I cracked on my 40th birthday because I hadn’t died yet. The End Times continue to drag out.

88 REASONS Why The Rapture Could Be In 1988 & ON BORROWED TIME (Two Books in One) by Edgar C. Whisenant is the booklet that circulated the UPC sect creating mass hysteria. I remember week-long revivals requiring daily attendance; I was baptized to cleanse the body of sin so I might get to heaven. <br/other did it and little sister wanted it too. There was no more time to be wasted. Hell is now.

All in the Name: How the Bible Led Me to Faith in the Trinity and the Catholic Church by Mark A. McNeil is the book my aunt Teresa bought for her three brothers to read and discuss with her. The author is a former United Pentecostal believer. We were all taught not to read what does not align with UPC beliefs; not all of us who did anyway abandoned religion, some changed teams; and some of us developed CPTSD with religion our kryptonite. Inside is tucked a blue feather I “found” on the Chehalis Western trail on the same day I read the story of the blue feather in the book Illusions: The Adventures of a Reluctant Messiah by Richard Bach. My aunt could appreciate what <f/>other can not.

A bundle of white sage to absorb harmful energy, paired with a white quartz for cleansing negative energies and promoting spiritual growth.

Underberg for digestion to ease the pain.

A rhino patch to remind of strength in sensitivities; one of the few remaining gifts from my ex-husband.

A full matchbox from Anna’s in New Orleans where unconditional love sparked.

A collaged rock to ground me in creativity.

A hexagon Orgonite to generate safety and compassion, achieve balance, and relieve homesickness.

A potpourri coffin scented with peace and gratitude.

These are items only I can apply meaning to and transfer power to control my beliefs. With these items in symbolic ritual, I strike a match and true love wins; the hell fire that threatens eternal damnation combusts the body to ash.

i /\m: present

I’m Not Wearing Any Pants: Undressing a Diagnosis is the only book I ever wanted to write before I die.

Some in my family believe that personal journals must be burned before death or left in the will to someone who will burn them with immediacy post-death; privately penned thoughts of the dead, meant to stay hid, off limits to the living. As a memoirist, I am diametrically opposed; thoughts released in a stream of consciousness can be a great teacher, identifying lessons outstanding and revelations. As a Gurley descendant, I will publish what I can before I die.

The debt is paid, this life is forgiven—the devil, released—to be lived. The soul will rapture when the body completes the cycle of living. May the publication of I’m not Wearing Any Pants: Undressing a Diagnosis end the spiritual torment and may death hold no secrets under lock and key.

i create the conditions to lessen the power of the triggers

these flashbacks of memories to be forgotten.

Crucify me, I don’t care.

don’t care what you think

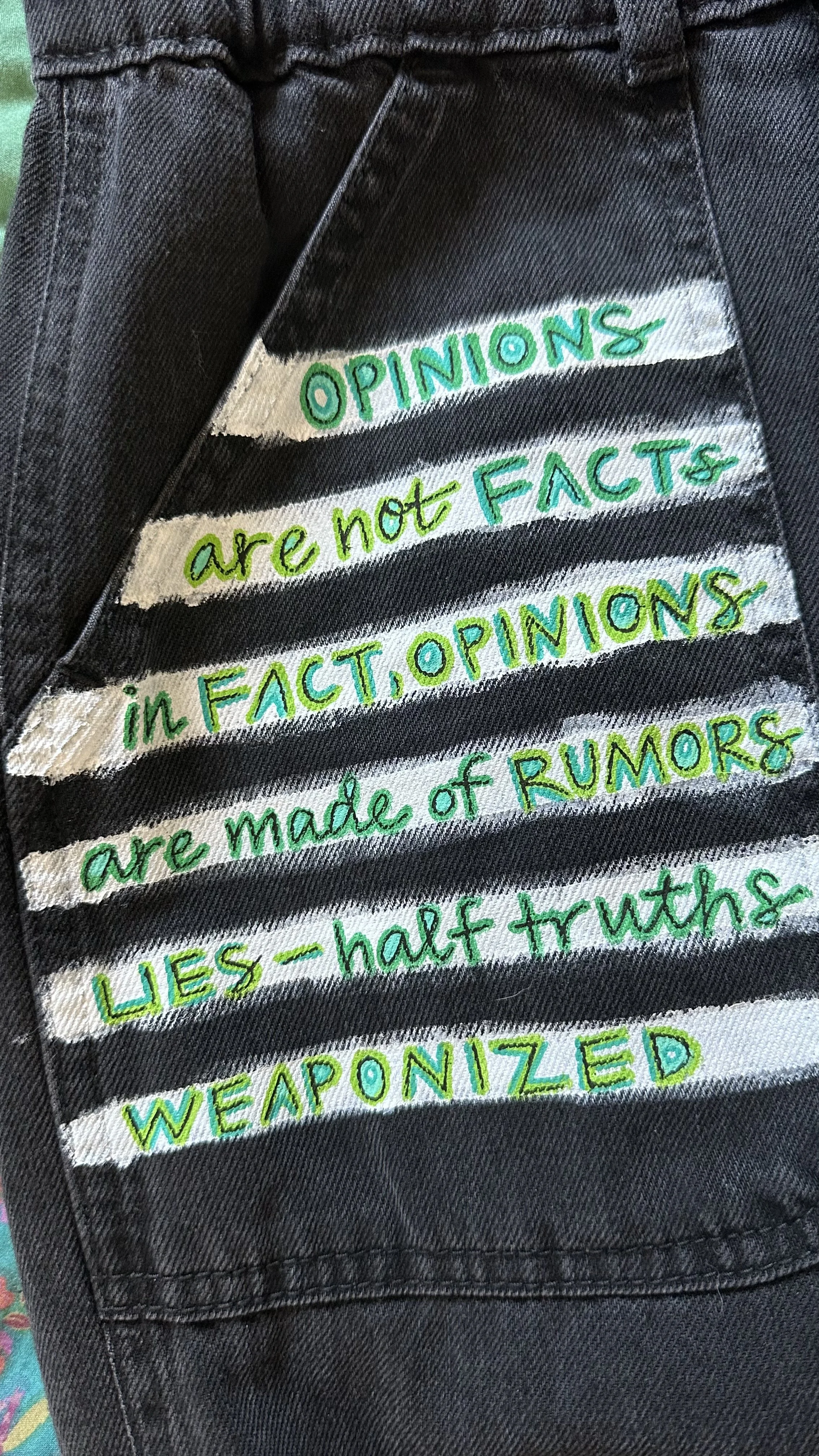

opinions are not facts in fact, opinions are made of rumors, lies—half truths weaponized

you are missing parts of the story, including what i have seen and felt and heard and thought and done; the ways

i /\m: healed

i manage the change and what i can control

while you spin a web to contain my essence and drain my energy;

you feed on me what you cannot create in you

i own the key to my soul

a copy is not original

no two the same and yet

we reflect

hell bound queer solo polyamorous asexual woman tattooed divorced estranged aborted a seed to save me raped of consent and of religious freedom PTSD

conquerors unwelcome;

love is free

generated inside of me and i have all i need

what you give i will receive but your love doesn’t complete me

fight first fawn apology freeze to breathe collect rest for flight

i don’t care what you think

i release the need to please

wearing my open heart on my sleeve

a testament of faith, witness my strength

i don’t need your god

i /\m: my own

i don’t care what you think

of me

i will live what i believe

love is all we need to stop the bleed

I throw myself on the sword of contradiction and I do not die. Secrets revealed cauterize the wound. The truth will set you free, or so we say. The truth has made me an island with limited passageway.

The wisest words from the mouth of a man 10 years less in age. “I don’t care.”

Not to care sounded harsh on the ear and bitter on the tongue. Selfishness centered, implied.

selfish doesn’t matter

i /\m: the center

You don’t have to understand me to love me,

and i wish you’d try.

as he turns his back and walks away, she affirms his reaction. “when he says he doesn’t understand you, he really doesn’t.”

of her own inability to listen, even to words on a page. “it’s too difficult to read what you write.”

her tears do not wash away his sins.

misunderstandings linger in the air; it is too much life to pretend doesn’t exist because they do not consent to engage in hard conversations where they might experience “bad feelings”.

what of the bad feelings i experience? must i be alone with them? i am a ghost.

I grew up confessing my sins at a church altar, begging forgiveness with other members of the sect. I did not speak them directly to a person, but I did speak them out loud to Godman in the sky so those around me could hear if Godman blessed my tongues with the holy language that proves salvation. People don’t forget as easily as someone who isn’t real, the sins you are vocally repenting from. Those sins become identity; with every mistake, you will be reminded because you outed yourself in the practice of repentance, another step in becoming saved. Our sins branded us. I was exposed to collective grief of suffering imposed;

die daily, confess and be changed!

Adults’ writhing bodies, loose tongues nonsensical, exhaustive wailing; we could only dance with the holy spirit,

there is joy in this pain!

I spar with myself. We are wrong, and we have the right answer, but we cannot forget our wrongness. I was born into sin, and I am a special one, born into the “truth”. Being human is traumatic, sinful; and I cannot be anything other than human. Is life a losing game? The Jesus character proved that living by your own compass will get you killed. His death is worshiped, his followers addicted to losing their lives, consent to murder. Do not kill, a commandment ignored.

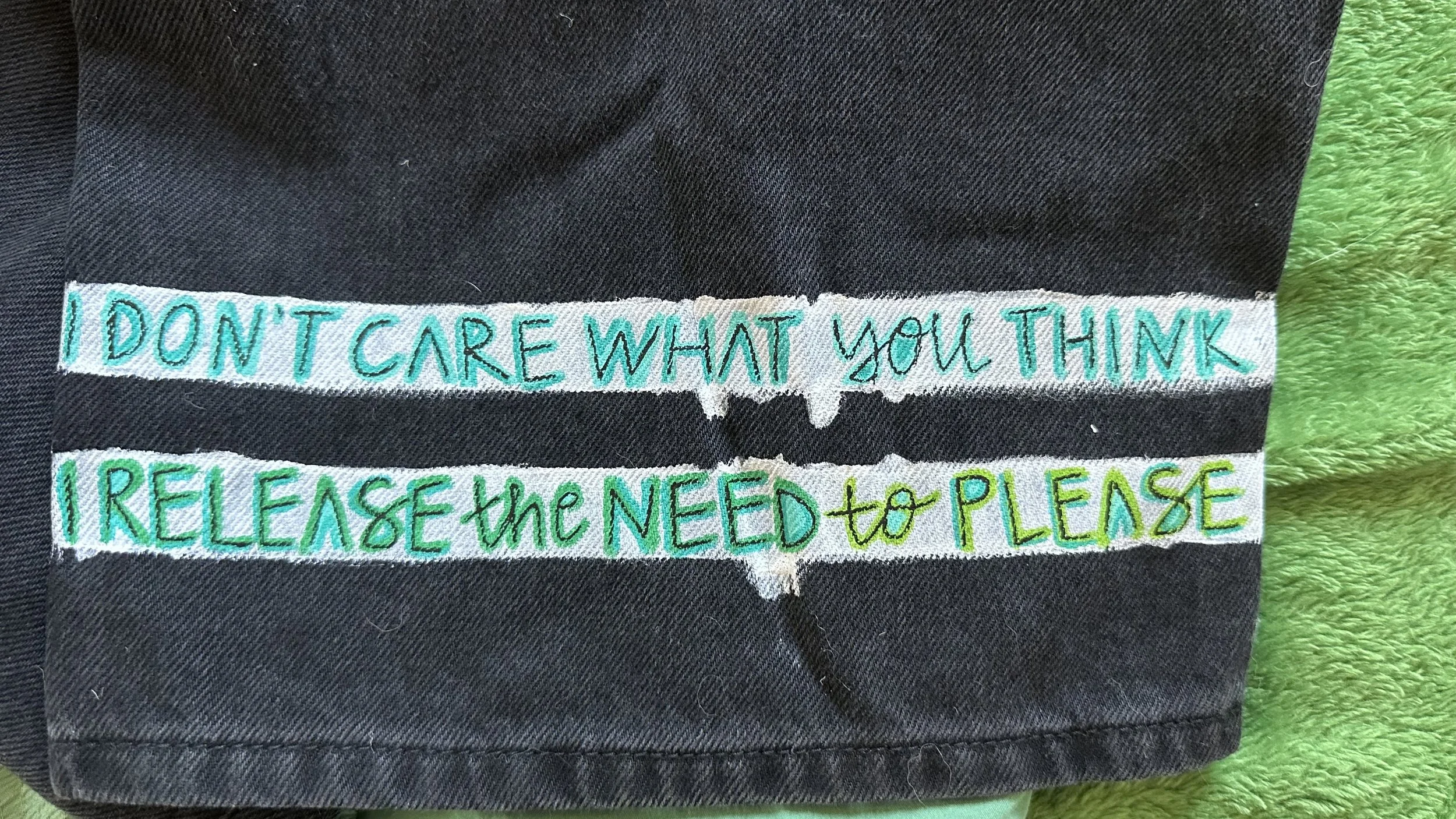

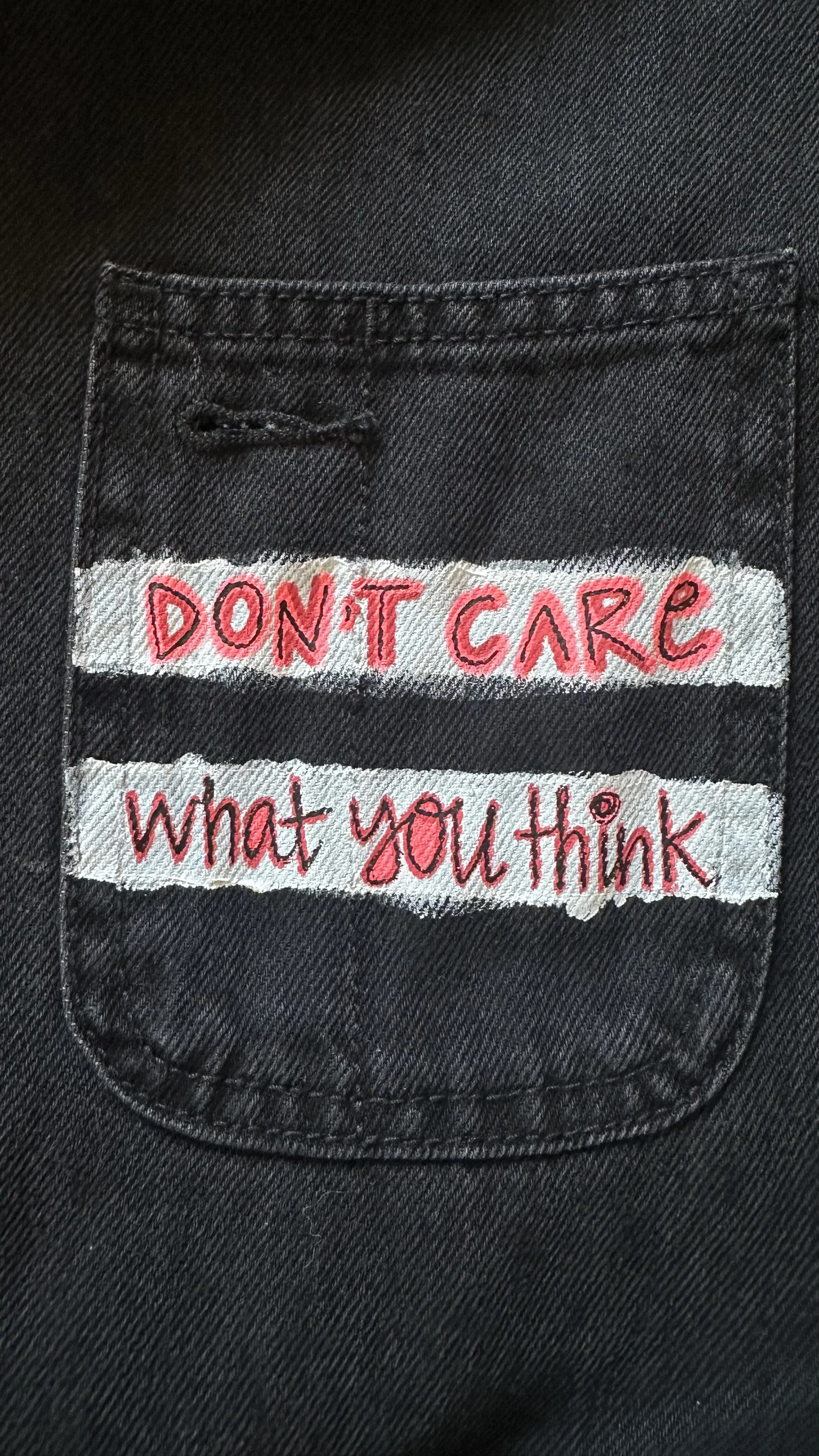

The hand painted black jean jumpsuit is a self-portrait.

White lines cut through the dark representing light, and lines of notebook paper. I stream my consciousness in color.

It has taken until my 40s to internalize not caring what others think. I lay hypervigilance on the altar, beside external perceptions, assumptions, interpretations and expectations. The anxiety lessens. I begin to highlight in me what gives another pause. I have nothing to hide when I am not pretending to be someone else. I cannot concern myself with ideals; I am only scared of heights when on a pedestal.

Wearing the jumpsuit in public draws others to me. I am commended for my bravery, uplifted in my artistry, and separated. You love me until the words become clear. The expression haunts, and that is the point. We cannot get away from ourselves, so I choose to run toward myself because I am with me all the time.

when i /\m: with me

i /\m: saved

So no, I don’t care what you think,

even if it kills me like it did that prophet.

History isn’t Destiny: Three words make a sentence.

I haven’t spent a morning with a book in months; there is no time for leisure pursuits. I reprimand myself for being still in body and empty of thought—motionlessness, a sin. I self-medicate with distractions “to turn my brain off,” though my preference in waking life is mindfulness. Who am I kidding? The voices ruminate as a tape on loop. I cannot escape myself and I cling to dissociative tendencies.

A brief meeting.

I met Catherine Gammon on Sunday, October 12, at City of Asylum for Books & Bistro, a gathering of local authors, poets, and independent publishers. There was promise of connection, which is why I attended, though these events usually serve to remind me how alone I can feel in this craft. I do not understand all the reasons I shy away from creative spaces, except to say I struggle to “know my place,” and contrary to popular opinion, I am quite frightened of recognition in real life. My talents have been squandered, so I have grown the belief I must keep them to myself while also harboring a desperation to be seen.

Gammon is nearly twice my age. I first saw her read at Bottom Feeder Books, on the evening of August 30, from What is your work? published by Almost Perfect Press. I was drawn to her immediately because of her whitened hair; I am intrigued with aging, less afraid, when I witness older women engaged in the arts. From where I sat, underneath a table, the small room crowded with bodies emitting smells of sweat and camaraderie, my knees tucked into my armpits, I closed my eyes and, when Gammon spoke, I imagined her presence as my future. Like her, I will grow older; like her, I hope I continue the work.

I approached Gammon at her table in City of Asylum, excited to see her. She had left Bottom Feeder before I was able to ask for a personal inscription in my copy of What is your work?. “I saw you a few weeks ago, at the Almost Perfect Press book release.”

Unsurprisingly, the sentiment she shared in response was familiar. I do these events but they are quite nerve-racking. I agreed. Many writers appreciate the opportunity to share and have a bent for privacy. I enjoy when I can be familiar to many and known by few. Writers reveal the stories we tell ourselves. It is not difficult to find those willing to relate when your words are clear and unavoidable.

I spoke with Gammon of the other books she had on display. On the back cover of Isabel Out of the Rain, published in 1991, was a portrait of Gammon. I asked her what it was like to have a book published so many years ago, and how she was connected to it now. What did it feel like to see herself as she was then, a young writer? The manuscript is on a floppy disk somewhere. I have thought about revisiting the work and making some edits. She inferred she would have no idea how to bring it back to life except to use a printed copy to create a file she could manipulate. Without hesitation, I offered that if she gave me a copy of the book, I would do it for her. “And I type fast.”

She commented nothing of her age and the 34-year old portrait, except to say she was in her 80s now. We exchanged information and she emailed me a few days later to thank me for the offer. She would consider it when she was ready to move forward with Isabel.

History isn’t destiny.

In the post-Thanksgiving lethargy, I was moved to read The Gunman & the Carnival while drinking coffee in bed. I lingered over Gammon’s handwriting and my first name written in proper, hurried cursive. “I hope you enjoy it,” signed, Catherine Gammon.

The coffee never stays warm enough because consuming words fills me up. I reheat in the microwave but the coffee doesn’t taste fresh, and my mouth is bitter with morning breath. The tongue is dirty, and I have a clear mind; the brain a sponge. On page 16, in A Vampire Story?, a single sentence stands out from the rest. “History isn’t destiny.”

Inspiration tickled my creativity but I told myself to keep reading. It is rare to find a book I have read that does not include underlines and highlights and notes in the margins. When I finished the editing certification program at University of Washington, Seattle, in 2018, the editor in me came alive and shadowed the writer in me, who could read for pure enjoyment. I read 11 more pages before scratching the itch. Extracting a single sentence from someone else’s work is a writing practice that helps me mine for deeper understanding of self.

I dialogued with my past,

it is true i feel relegated to past versions of myself, as if i owe her something. she wonders when i will grow wise to my own nature. she sees my tendency to hide and keep secrets—to live up and into another’s ideal silently, accepting the stories they weave and trying to fit herself into them. i am as beautiful as they say, but she never lets it go to my head.

“i couldn’t if i wanted it to,” i tell her.

she nods. “it’s your dad’s fault, and your mom’s, you don’t believe. and what if you could?”

“i know, i know, the blaming ages me. what of forgiveness?”

“you don’t have to give it to them, only to yourself.”

“what’s in it for you?”

“death.”

“i am not ready to die, though i think of it often. i picture what i might look like when i am stiff.”

“death is not rigid.”

“oh, you are going to tell me it is peaceful. you know that only makes me want it more.”

“i don’t blame you. the only way i will disappear is when you forgive yourself for not being perfect. otherwise i will haunt you forever.”

“and forever haunting is something i shouldn’t want? it’s nice to know i will always have company.”

and shared the piece with Gammon.

When the stream-of-consciousness quieted, I emailed Gammon. “I hope an unsolicited share isn’t unwelcome.”

I wondered if she might be interested in discussing writing over coffee or tea, before closing the note with my digital signature. I await response without expectation, only gratitude. Gammon’s discipline to the craft over the years has shown me a glimpse of who I might be when I “grow up,” and I don’t know anything about her journey. I don’t know anything of myself at 80, but I think I want to.

History only informs the future if we are unwilling to change now.